“Matrescence like Adolescence”

Mother of Mothers

OriginAL SCHOLAR

Dana Louise Raphael (1926–2016) began her doctoral studies in anthropology at Columbia University under the mentorship of Margaret Mead. For her dissertation, completed in 1966 and published as The Tender Gift: Breastfeeding (1973), she researched how cultures around the world perceived breastfeeding compared to the United States.

Raphael introduced the term doula—from the Greek word for “woman servant”—to describe a supportive companion during childbirth. But tucked within the pages of The Tender Gift was perhaps an even more powerful word: matrescence. Both terms reflected her conviction that women’s reproductive experiences deserved social, cultural and emotional recognition, not only medical attention.

Raphael went on to co-found the Human Lactation Center, which held consultative status at the United Nations. She wore an IUD necklace as a symbol of reproductive empowerment and expanded her advocacy to include climate change. Always ahead of her time, she challenged cultural blind spots and planted the seeds for concepts that would gain momentum decades later. Her legacy must be honored by advancing the science of matrescence even further for the 21st century.

To our Mother of Matrescence, we thank you.

Reviving Matrescence

Continuing its Theorization

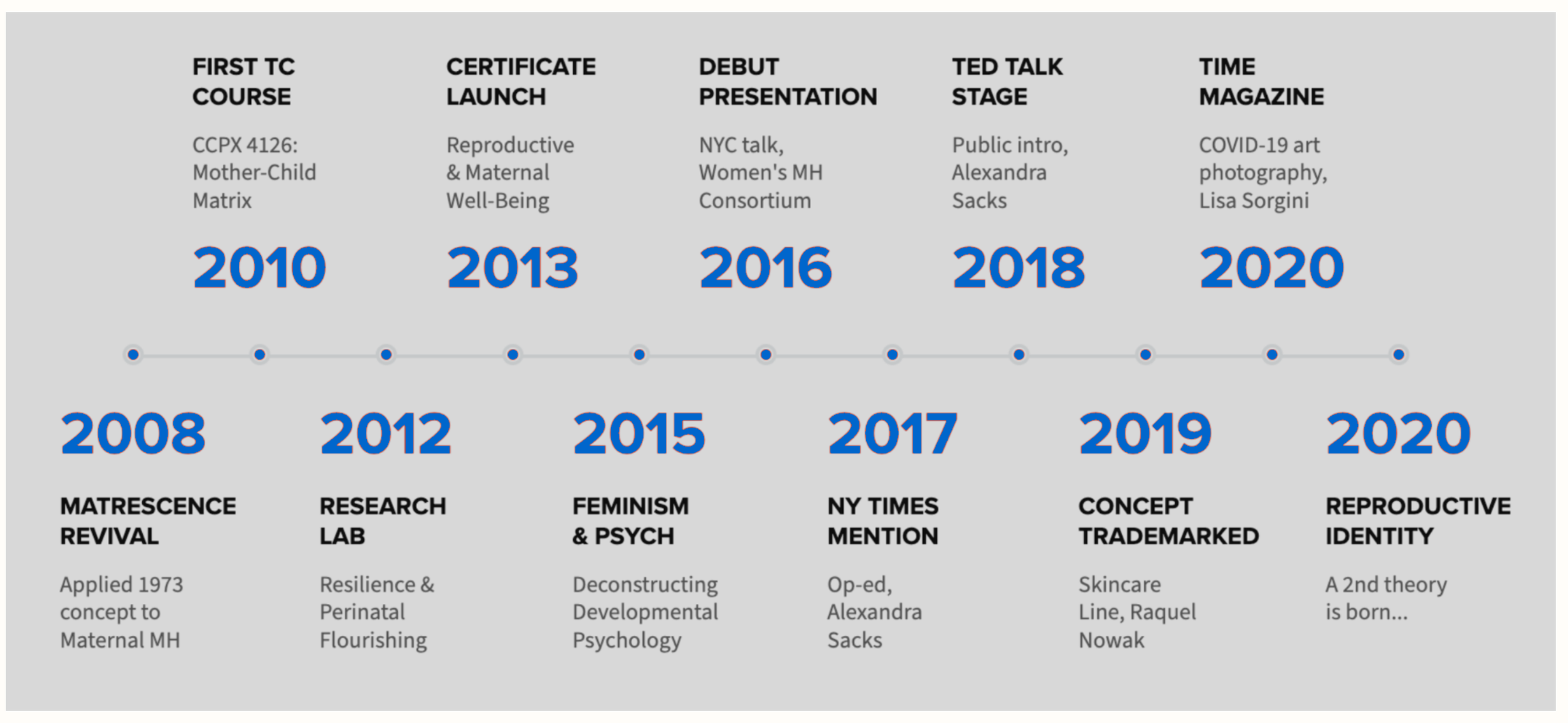

Matrescence, the developmental transition to motherhood, was first introduced in the 1970s by anthropologist Dana Raphael, Ph.D., who sought to give language to this profound life change. Yet the concept never fully entered the mainstream and for decades it remained largely unknown. I sought to revive and reinterpret it for our modern era.

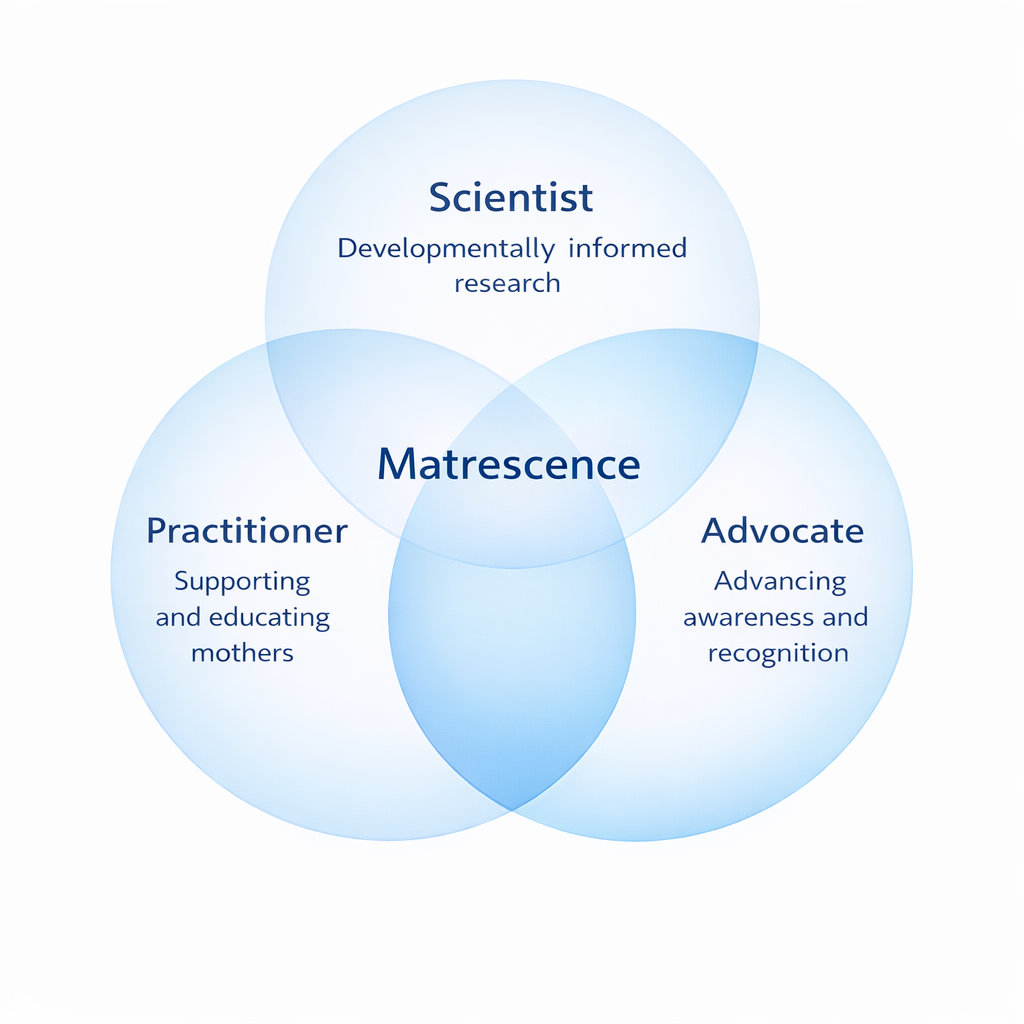

I am Dr. Aurélie Athan, a clinical psychologist and faculty member at Teachers College, Columbia University. Building on Raphael’s pioneering insight, I systematically expanded her original definition and reestablished matrescence—a normative stage of development comparable in significance to adolescence—and essential to scientific inquiry and public understanding. Fifty years after its introduction, my contemporary framing complements existing clinical models of maternal mental health by recognizing mothers holistically, holding both resilience and distress as integral aspects of becoming a mother.

Today, I am often asked: “What is it like to see your efforts catch on as it has?” I offer them another single word: Wild. From podcasts and popular books to academic symposia to technology startups, matrescence is now spoken in therapy rooms, birth classes, research labs, media platforms, and living rooms. I could not have fully anticipated such an explosion of interest— though I sensed the hunger for a word that names this transformation with dignity and depth. We are now witnessing a true revival.

Please join me in stewarding this effort with integrity. It is a great responsibility.

THe SCIENCE OF MATRESCENCE

Reviving the word is only the beginning...

Beyond providing language, the deeper work lies in advancing the science of matrescence and embedding this framework into health care, research, and policy. To carry matrescence forward means moving beyond a conceptual idea and into measurable frameworks, educational programs, and public health applications. It requires rigorous research and collaborative partnerships across the biomedical, social, and political sciences. By grounding matrescence in evidence and practice, we not only validate women’s lived experiences but also create sustainable pathways for improving their lives across diverse contexts and cultures. Matrescence must become more than a feel-good movement if it is to have a lasting impact.

“In my expanded definition, the process of becoming a mother or matrescence, the term first coined by Dana Raphael, Ph.D. (1973) and which I later built further upon, is a developmental passage where a woman transitions through pre-conception, pregnancy and birth, surrogacy or adoption, to the postnatal period and beyond. The exact length of matrescence is individual, recurs with each child, and may arguably last a lifetime! The scope of the changes encompasses multiple domains— biological, emotional, social, political, spiritual— and can be likened to the developmental push of adolescence. These transformations unfold in both “brain and mind”: the maternal brain undergoes measurable morphological and functional reorganization, while the mother’s inner world undergoes profound psychological and ideological restructuring—reshaping her identity, beliefs, values, priorities, and sense of meaning or purpose.”

- Definition written by Aurélie Athan, Ph.D. (2016, updated 2026)

What is Matrescence?

My Working Definition

To attribute [APA Style]: Athan, Aurelie. (Year, Month, Day of D/L). Working Definition. https://www.matrescence.com/

“Childbirth brings about a series of very dramatic changes in the new mother’s physical being, in her emotional life, in her status within the group, even in her own female identity. I distinguish this period of transition from others by terming it matrescence to emphasize the mother and to focus on her new life style.”

— Dana Raphael, The Tender GIFT: Breastfeeding (1973)

“The critical transition period which has been missed is matrescence, the time of mother-becoming...Giving birth does not automatically make a mother out of a woman...The amount of time it takes to become a mother needs study.”

— Dana Raphael, Matrescence, Becoming a Mother, A New/Old Rite de Passage (1975)

50 years later

“A more comprehensive understanding of matrescence suggests that the transformations that occur during preconception, pregnancy, birth, surrogacy, adoption, and early parenting can affect every domain of human life experience, above and beyond those initially identified by Raphael. I describe it as a holistic phenomenon, or a lifespan, developmental transformation that is biological, neurological, psychological, social, cultural, economic, political, moral, existential, ecological, and spiritual in nature. This expanded conceptualization is essential for facilitating a thorough understanding of motherhood that may more aptly explain the decline in maternal well-being observed today.”

— Athan, 2025

“What makes matrescence distinct from adolescence is that its length varies among individuals, it may reoccur with each new child, and may have an acute stage followed by a more complex, and longer process with no definitive end (e.g., grandmothering). It has been suggested that integrating developmental psychology terms like “emerging motherhood” (infancy to school age), “middle motherhood” (adolescence), and “late motherhood” (adulthood) could enhance our understanding of the evolving stages within this lifelong transition.”

— Athan, 2025

Domains of Change

Improving maternal well-being: a matrescence education pilot study for new mothers. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology (2025)

Big idea, For Greater Good

Increased attention to mothers has spurred new findings, from neuroscience to economics to name a few, and supports the rationale for a new field of study known as matrescence. Such an arena would allow the roundtable of specialists to come together and advance our understanding of this life passage. Formalizing this area of inquiry would create space for interdisciplinary collaboration and allow us to advance knowledge with greater coherence and impact.

Call to Action: If you are a scholar, researcher, clinician, educator, or practitioner who supports the development of matrescence as a recognized interdisciplinary field, we invite you to add your name in endorsement. You may also share a brief statement and links to your relevant work or publications.

As opportunities arise to bring this collective vision to policymakers, funding agencies, professional societies, or scientific organizations, we aim to demonstrate that the intellectual groundwork is already underway. If there is sufficient interest, we may include you in a public-facing directory in the future.

Social IMpact

Advancing the science, then shaping how society understands it

History

A missing Framework

It all began with a gap. During my doctoral training in the 2000s, I was struck by the absence of models that could explain the psychological transition to motherhood beyond frameworks rooted in psychopathology and clinical diagnosis. None captured the full range of experiences voiced by the mothers I interviewed about their spirituality for my dissertation. Determined to find a more balanced understanding, I began looking beyond my own field for answers.

Fast forward: as a new faculty researcher grounded in positive psychology, I began working with my students to systematically review decades of research on the transition to motherhood. What we found was revealing—mothers were rarely the focus of study, described mostly through the lens of risk, illness, or their impact on children, and almost never in terms of their own strengths, growth, or thriving.

Finding Matrescence

I drew on the intellectual lineage of maternal developmental theorists, but it was Dana Raphael—another Columbia-trained scholar—who offered the conceptual key to what had been missing.

Recognizing the power of her idea, my contribution was to bring the existing concept of matrescence from anthropology into psychology, challenging the narrow maternal mental health paradigm in which I had been trained. Knowledge advances when we bridge fields—quiet, behind-the-scenes work in academia that rarely makes headlines, yet is essential.

A Holistic transition

Raphael described motherhood as a biosocial transition, noting that its psychological dimensions needed further study. I built on her foundation by proposing a more comprehensive “bio-psycho-social-and-beyond” framework—one that touches every domain of human experience.

By 2010, I reintroduced her term through an intentionally designed public health slogan: matrescence, like adolescence. This simple yet memorable phrase proved successful and soon became a sticky teaching tool within and beyond academia, helping to normalize, rather than pathologize, the transition to motherhood.

for the Next Generation

In 2015, I joined scholars critiquing the field of developmental psychology for marginalizing mothers in its theories. I published Maternal Psychology: Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Deconstructing Developmental Psychology in a special issue of Feminism & Psychology.

Building on Erica Burman’s landmark work, I argued that introducing the term matrescence—and positioning it as a distinct phase of the human lifespan—could legitimize motherhood within the scientific community and provide a framework for the next generation of scholars to reimagine their research questions.

I envisioned a future where specialists from neuroscientists and physicians to counselors and educators would gather at a common roundtable, united by matrescence, to form an allied discipline with a shared purpose much like adolescence.

AcademiA to the World Stage

In October of 2016, I presented my argument at a pivotal NYC conference of the Women’s Mental Health Consortium. Only a few months later, on Mother’s Day 2017, my talking points entered the popular imagination through Alexandra Sacks’s widely read New York Times article: The Birth of a Mother and later TED talk. This marked a turning point, as mothers responded overwhelmingly positively to finally having language to describe their experience!

Continuing the Legacy

Since beginning this revival effort, matrescence has spread globally, taken up and amplified by many voices across disciplines and cultures. The term now circulates widely—from social media conversations to community initiatives, and even through costly products marketed to mothers with promises of enlightenment.

Yet amid this broad diffusion, my hope remains the same: that matrescence helps recognize and destigmatize the full spectrum of maternal experience, from stress to wellbeing.

Today, we hear it echoed in far corners we never imagined it would reach—an idea seeded with the hope that it might take root in mothers’ minds and begin to reshape their self-concept and the society around them. May its true promise extend beyond a feel-good movement to catalyze real, tangible improvements in maternal well-being—so that we may never again hear the refrain, “Why didn’t anyone tell me?”

TimelinE of Matrescence

Matrescence Education

At the Khora Lab, our mission is to advance maternal health literacy through the power of education and to innovate public health approaches with new frameworks such as reproductive identity development.

As a social impact lab, we aim to equip both mothers and the professionals who care for them with the knowledge and tools to recognize, prepare for, and support matrescence with competence, confidence, and compassion—so that no woman faces motherhood without understanding or language for her experience. Most of all, we affirm an ethical commitment to improving mothers’ wellbeing and nurturing their human potential, to treating them as a vulnerable and protected class, and to never profit from their distress or hope for growth.

We Stand On The Shoulders of Maternal ScholarS